Amelia and her navigator, Fred Noonan, disappeared while attempting to fly across the Pacific Ocean in a Model 10E Lockheed Electra. They took off from Lae, New Guinea on the morning of July 2, 1937, heading for tiny Howland Island, some 2500 miles away, and were never seen again. The group TIGHAR promotes the Nikumaroro Hypothesis — that having failed to find Howland, Earhart and Noonan landed the Electra on Gardner Island, now known as Nikumaroro, a then-uninhabited atoll located 400 miles to the southeast of Howland. The Nikumaroro Hypothesis further supposes that a few days after Amelia landed the Electra on Nikumaroro’s fringing coral reef the plane was washed into the ocean and that Amelia and Fred died on Nikumaroro in the following weeks or months.

In support of the Nikumaroro Hypothesis, TIGHAR points to the story of the discovery of the remains of a castaway on Nikumaroro in 1940, not long after the island was settled by colonists from the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony. The settlement of Nikumaroro was carried out under the supervision of Gerald Gallagher, a British colonial official, in what was one of the final acts of expansion of the British Empire. In September, 1940, Gerald Gallagher informed his superiors that the partial skeleton of a castaway had been found earlier in the year by a colonist work party, presumably while they were clearing vegetation for the planting of coconut palm trees.

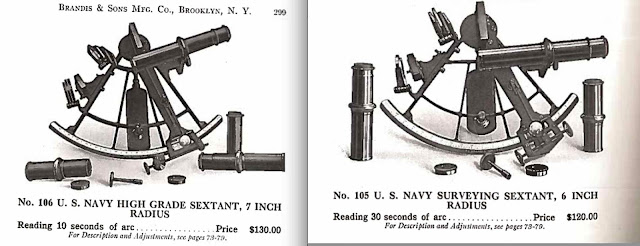

Gallagher reported that searches of the vicinity of the castaway’s remains turned up several items, including a fragment of what he took to be a woman’s shoe and an empty sextant box marked with two four-digit serial numbers — 3500 and 1542. Gallagher suggested to his superiors that the castaway might have been Amelia Earhart. Gallagher’s superiors took this suggestion seriously and had the bones and items found near them sent to them for further analysis. A doctor named David W. Hoodless, who taught at the Central Medical School in Fiji, examined the bones and concluded that the castaway had been a short, stocky male. The sextant box was examined by Harold Gatty, a world-famous pioneer of air navigation who happened to be in Fiji. It is clear from Gatty’s remarks that he understood that he was being asked whether the sextant box could have come from Earhart’s Electra. Gatty’s opinion was that the sextant box could not have been that of a navigation sextant used in modern aviation — ‘modern’ here meaning the late 1930s. With the possibility of the castaway being Amelia Earhart ruled out, there was no further interest in determining the identity of the castaway.

In 1998 TIGHAR had Dr. Richard Jantz, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Tennessee, reanalyze the bones measurements made by Doctor Hoodless during his 1940 examination of the castaway’s bones (the castaway’s bones and the other items found nearby have long since disappeared). Jantz cautiously concluded that the bones were ‘more likely female than male’ and were ‘more likely white than Polynesian or Pacific Islander’ [1]. This wasn’t exactly a resounding affirmation of the Nikumaroro Hypothesis, but TIGHAR made much of Jantz’s findings, sometimes neglecting to indicate the degree of uncertainty in Jantz’s conclusion. In 2015 Pamela Cross of the University of Bradford and Richard Wright of the University of Sydney published a paper disputing Jantz’s conclusions, arguing that there was no reason to disbelieve Dr. Hoodless’s original conclusion that the castaway was a man [2]. In response to the Wright and Cross paper, Jantz conducted a new re-analysis of Dr. Hoodless’s notes, and this year published a paper that essentially concluding that there is a high probability that the castaway was Amelia Earhart [3]. I’m not a forensic anthropologist and the subject of this post is the Nikumaroro sextant box, so I will leave the question of whether the castaway was a short, stocky man or Amelia Earhart to those who by training are better qualified to address it.

So now onto the matter of the Nikumaroro sextant box. The British colonial officials to whom Gallagher sent the sextant box understood that the four-digit numbers it was marked with might allow them to determine the box’s origin, but since they had determined that the castaway wasn’t Earhart this line of investigation was never pursued [4]. TIGHAR took up the challenge of using the serial numbers to trace the sextant box numbers to its owner. It was eventually learned that the sextants used by the United States Navy in the early decades of the twentieth century are marked with two serial numbers. One serial number is the sextants manufacturer, and the other is a serial number assigned by the U.S. Naval Observatory, which had the task of inspecting and maintaining the U.S. Navy’s sextants.

|

| Brandis Sextant, Brandis Serial Number 3985 |

|

| Same Sextant -- its Naval Observatory Serial Number |

The boxes made to hold these sextants are marked with the manufacturer’s serial number of the sextant they originally held; some are also marked with the sextant’s Naval Observatory serial number. The pair of numbers on the Nikumaroro sextant box, 3500 and 1542, match up well with serial number pairings on surviving examples of U.S. Navy sextants made by one particular sextant manufacturer, Brandis and Sons. If 3500 was a Brandis serial number and 1542 a Naval Observatory serial number, there was good reason to think that the Nikumaroro sextant box once held a Brandis sextant made for the U.S. Navy. As discussed in my earlier posts on the Brandis serial number chronology, a Brandis sextant with serial number 3500 would have been made around the time of the First World War.

How could a World War One era Brandis nautical sextant box be connected to Amelia Earhart’s final flight? TIGHAR proposed that the Nikumaroro sextant box once belonged to Fred Noonan, Amelia Earhart’s navigator. Noonan had been a navigator on the Pan Am Clipper seaplanes that were the first to provide passenger air service across the Pacific Ocean. On those flights Noonan used a bubble octant, a kind of sextant made specifically for air navigation, to stay on course for the tiny islands that Pan Am Clippers would stop at to refuel when crossing the Pacific Ocean. It is reasonable to think Noonan used a bubble octant to navigate Earhart’s Electra [5]. Bubble octants were quite unlike the nautical sextants that Brandis made during the First World War and so were the boxes used to store them. When Harold Gatty remarked that the Nikumaroro sextant box could not have been used for modern air navigation, what he presumably meant was that the Nikumaroro sextant box was not made to hold a 1930s air navigation octant.

While Gatty’s remarks seem to rule out the possibility that the Nikumaroro sextant box was Noonan’s, TIGHAR points out that in a letter describing his navigational techniques while working for Pan Am, Noonan wrote: “Two sextants were carried – a Pioneer bubble octant and a mariner’s sextant. The former was used for all sights; the latter carried as a ‘preventer’ ”. It is not clear what Noonan meant by ‘preventer’. TIGHAR speculates that Noonan meant that he used a mariner’s sextant as a back-up for the Pioneer bubble octant that was his primary navigating instrument. TIGHAR further suggests that Noonan’s mariner’s sextant was made by Brandis, offering as evidence a photograph of the navigator’s station of a 1930s Pan Am Clipper in which a box that looks like a Brandis nautical sextant box can be seen. Since traditional nautical sextants were poorly suited for air navigation, TIGHAR further speculates that Noonan’s Brandis sextant had been modified into a Byrd sextant, an early version of an air navigation sextant; a sextant so modified would still fit in its original box. TIGHAR further speculates that Noonan had his Brandis-Byrd sextant with him on the lost flight to Howland Island, and that it is the box for this sextant that Harold Gatty passed judgement on in Fiji in 1940.

The case TIGHAR made for the Nikumaroro sextant box being Fred Noonan’s is a circumstantial one, but it nevertheless was plausible. The big problem with it is that TIGHAR has never been able to prove that Fred Noonan actually owned a Brandis sextant, much less that he had one with him when he and Amelia Earhart disappeared on their way to Howland Island.

I began to follow TIGHAR in 2012, and the hypothesis that the Nikumaroro sextant box belonged to Fred Noonan was of particular interest to me. At some a point an alternate hypothesis for the origin of Nikumaroro sextant box occurred to me. In late 1939, only a few months before the castaway’s remains were found, the USS Bushnell, a U.S. Navy submarine tender outfitted as a hydrographic mapping vessel, visited Nikumaroro to survey the island and its lagoon. My alternate hypothesis was that a Bushnell surveyor inadvertently left the box for the Brandis sextant somewhere in the vicinity of the castaway’s remains, where it was found a few months later in the search for the castaway’s personal effects. Much of Nikumaroro is covered in forest and scrub and so it is conceivable that a Bushnell surveyor could have passed close to the castaway’s remains without seeing them.

Documents available on the TIGHAR website show that the Bushnell’s surveyors had set up a network of reference points throughout the island for the surveying work they were doing [6]. Some of that work involved measuring water depths from small boats making transects across the lagoon. It occurred to me that the Bushnell surveyors might have determined their position when making these transects by using sextants to triangulate on the land-based reference points they had set up. A hydrographic surveying manual published by the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1931 confirmed that sextants were in fact used in this way [7].

So, sextants could have been used by the Bushnell surveyors on Nikumaroro, the boxes for those sextants could well have been marked with Brandis and Naval Observatory serial numbers, and a Brandis sextant box left on Nikumaroro by the Bushnell in late 1939 would have been there in time to be found after the discovery of the castaway in 1940. When I offered up my alternate hypothesis on TIGHAR’s discussion forum, Ric Gillespie, TIGHAR's Executive Director, responded dismissively and with downright hostility, something he often did when a tenet of the Nikumaroro Hypothesis was in some way threatened. To give a sense of how that went I’ll mention that at one point, after I suggested that TIGHAR should search for records that might indicate whether a sextant with serial numbers 3500 or 1542 was issued to the Bushnell, Gillespie’s response was to say any such effort would be ‘wasting time on snipe hunts’; he also said that my hypothesis was ‘thoroughly bizarre’ and that I should ‘go do some real research’ [8]. In the rest of this post, I’ll discuss what Ric might have learned had he spent a few afternoons researching the USS Bushnell at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., a two-hour trip from his home.

My first National Archives trip was in December of 2016. If the Bushnell’s surveyors had used sextants to determine position while surveying Nikumaroro’s lagoon, I had reason to think that they would have recorded the serial numbers of the sextants they used. The 1931 U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey’s Hydrographic Survey Manual showed an example of a data sheet for a hydrographic survey on which serial numbers of the sextants that were used are recorded (see photo below). My goal was to find if something like those data sheets existed for the Bushnell survey of Nikumaroro.

|

| U.S. Coast & Geodetic Hydrographic Survey Data Sheet |

My first day was spent at the National Archives and Record Administration (NARA) facility in Suitland, Maryland. I knew that Suitland was a repository for maps produced by the U.S. Navy and so it seemed like a good place to look for the Bushnell’s field surveying records if they still existed. At Suitland I was able to find rough maps of the water depths of Nikumaroro’s lagoon that were produced while the Bushnell was still at Nikumaroro. The raw data from which these maps were prepared were not at Suitland, however. On the shelves of the Suitland reference room I found a decades-old finding aid for the records of the Bushnell’s hydrographic surveying work. The finding aid showed that the maps I found at Suitland and notebooks containing the data from which those maps were prepared were at one time kept together somewhere in a single collection. That collection had long since been broken up and the maps eventually ended up at Suitland. I was told that if the field notebooks for Nikumaroro still existed, they would be at the NARA archive in downtown Washington, D.C. The Suitland staff member I spoke with held out little hope that those notebooks would still exist.

At the National Archives in Washington the next day I had the good fortune of meeting Chris Killillay, a NARA staff member who has a deep knowledge of the U.S. Navy material held in the archives. I didn’t have file reference numbers that would help him figure out if the field notebooks I was looking for still existed, or where in the voluminous collection of U.S. Navy material held by NARA those notebooks might be. Mr. Killillay nevertheless had some ideas about where to look, and after disappearing into the file storage area for a while he came back out and told me that he had found the Bushnell’s field notebooks for Nikumaroro. I was gobsmacked. I filled out a request form to have the notebooks delivered to the NARA reading room and a little while later up in the reading room a cart came out to me loaded with box after box of Bushnell surveying notebooks, and not only for Nikumaroro but for many other islands that the Bushnell surveyed during its 1939-1940 surveying season.

It was amazing to have the Bushnell’s surveying notebooks sitting in front of me on a cart. I was probably the first person to ask for them in 70 years. I located the notebooks for Gardner Island and started to look through them. Inside there were pairs of preprinted pages on which the measurements needed for map construction were recorded. The photo below shows part of a typical two-page spread. On the left page are water depth measurements and the times at which the measurements were made, and on the right page are measurements of two angles, indicated as ‘left’ and ‘right’, made on three reference points, indicated as GAR, GUN, and WIT. The left angle was presumably that between reference points GAR and GUN, and the right angle that between GUN and WIT. At the end of a series of measurements on some notebook pages the words ‘sextants check’ were written, as can be seen in the second photo below.

|

| Notebook Pages from the Hydrographic Survey of the Nikumaro (a.k.a. Gardner Island) Lagoon |

|

| 'Sextants Check' on a Notebook Page |

Clearly, sextants had been used in surveying Nikumaroro. But much to my disappointment I was unable to find sextant serial numbers in any of the notebooks I looked through, either for Nikumaroro or for any other island that the Bushnell visited during that same surveying season. I didn’t have time to look through every page of every notebook but I had looked through enough of them to think it unlikely that sextant serial numbers were recorded in any of the notebooks. Apparently it was considered unnecessary to indicate the specific instruments used to make the measurements recorded in these notebooks. Rather than continue to look through the Bushnell’s notebooks for the 1939-1940 surveying season, I used the remaining time I had at the Archives to look at notebooks for the 1938-1939 season, during which the Bushnell conducted hydrographic surveys along the Caribbean coast of South America. I managed to find a notebook page that contained the entry ‘Sextant #2806 & #2810 checked’ (see photo below). Here were sextants with four-digit numbers, but the numbers weren’t 3500 or 1542, and it wasn’t clear whether 2806 and 2810 were Naval Observatory numbers or manufacturer’s serial numbers. I looked through other notebooks like the one in which the 2806 and 2810 appeared, but all of them were devoid of sextant serial numbers.

|

| Sextant Numbers on a Page from the Bushnell Survey of the Coast of Venezuela |

That was pretty much as far as I got on my first NARA visit. The upshot was that I found documentary evidence that Bushnell surveyors used sextants in their hydrographic survey of Nikumaroro, but there was no proof that those sextants were Brandis sextants, much less that one of them was Brandis #3500, USNO #1542.

My next NARA trip occurred in August of this year. A few months earlier a person named Lew Toulmin wrote a report about the findings of his research into the origins of the Nikumaroro Sextant box [9], which included research at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Toulmin examined an index card catalog for NARA’s holdings of U.S. Naval Observatory’s correspondence for the period 1909-1925. The card catalog was organized by subject, and one of those subjects was sextants. Each card gave a terse summary of correspondence in a Naval Observatory file and a file number that could be used to locate the actual correspondence. Toulmin found nothing on the cards he looked through that allowed him to determine the origin of the Nikumaroro sextant box. On this Archives trip I wanted to have a look at the 1909-1925 card catalog that Toumlin had already looked through, because I thought it would point me to Naval Observatory correspondence that would allow me to refine the Brandis serial number chronology that I’ve discussed in earlier posts. But I was also interested in a second card catalog that Toulmin hadn’t looked at, which was for NARA’s holdings of U.S. Naval Observatory correspondence for the period 1925-1943. My thought was that the Naval Observatory, in its role as the U.S. Navy’s sextant service shop, might have supplied the Bushnell with Brandis sextants, and the 1925-1943 card catalog might point me to documents attesting to this.

As I started to go through the index card catalogs in NARA’s reading room I quickly realized what a daunting task it was to glean information from them. There were a huge number of index cards on the subject of sextants and many of the cards were handwritten in a nearly illegible script. It was impossible to digest the information on the 1909-1925 index cards while sitting in the NARA reading room, so all I could do was photograph them so that I could decipher them when I got home. The 1925-1943 card catalog was easier to read, but I only found two index cards under the subject of sextants that seemed to have potentially promising leads. The first card read:

Sextants, patrol Bt. Brandeis - unfit for use - 144 turned in to N. Obvy - Supt. N. Acad. 1/14/37 - 2-2X3.

‘Brandeis’ was obviously a misspelling of Brandis, and I recognized ‘Sextants, patrol Bt.’ to be a reference to the 5-inch radius Brandis sextant that I wrote about in the post titled ‘Brandis Sextant Taxonomy, Part Five’. All the Brandis sextants of this type that I knew of had Brandis serial numbers in the 3000s, not far off from the presumed Brandis serial number on the Nikumaroro sextant box. Perhaps the full Naval Academy memo this card summarized actually listed the serial numbers of the Brandis patrol boat sextants that were turned into the Naval Observatory. In Brandis Sextant Taxonomy, Part Five I noted that sextants of this type had features that made them well-suited for hydrographic surveying. So when I saw this index card I wondered if the sextants were refurbished at the Naval Observatory and sent to the USS Bushnell. The Naval Academy letter was dated January 14, 1937, so there would have been enough time to get those sextants fixed and to the Bushnell in time for the voyage on which the Bushnell surveyed Nikumaroro.

The second index card read:

U.S.S. Bushnell - 1004 - Rq. for sextant mirrors - 24 Index + 24 Horizontal - C.O. 8/4/38. 2200.

6105 Yr. 1004 2200 Shipped this date P.P. Navobsy. Inv. 290 — To C.O. 8/5/38 1500

There was no mention of sextants in the terse summary written on this index card, but I wondered if the full message that the card summarized might say something about sextants. By the time I found these two cards it was too late in the day to have the files for this correspondence retrieved. My visit to the Archives had come to an end, and so I would have to come back another time to follow up on the two index cards.

It wasn’t until last week that I was able to return to the Archives and access the files that the cards referred to. I was disappointed to find that the full Naval Academy letter summarized on the first card said nothing about the serial numbers of the Brandis patrol boat sextants sent to the Naval Observatory. The correspondence on the second card also led nowhere; what was written on the card was basically the full extent of the correspondence, which apparently had occurred by telegram or radio.

The information on those two index cards led me nowhere; I had reached a dead end. Was there anywhere else in the Archives left to search? The two disappointing index cards were filed under the subject ‘Sextants’ in the card catalog, and I remembered that further along in the card catalog were cards filed under the subject ‘Surveying Instruments’. I went back through those index cards and found a few cards summarizing correspondence between the USS Bushnell and the Naval Observatory. The card in the photo below was particularly tantalizing. It summarized a chain of correspondence between the Bushnell and the Naval Observatory about surveying instruments that the Bushnell had sent to the Naval Observatory for repair in late 1938. I put in a request for the files for this correspondence, but the file boxes that came to up to me in the NARA reading room didn’t contain the corrspondence I was looking for. Chris Killillay was on duty when I went downstairs to the room where NARA archives specialists meet with researchers, and I told him that I had been unable to find the correspondence I wanted. He went into the file storage area for a while, and when he came out he helped me fill out a request form for a file box that he thought was the only one left in the Archives that might hold the correspondence I wanted.

|

| Index Card from the USNO Correspondence 1925-1943 Card Catalog |

A little further into the chain of correspondence I came upon a four page memo from the Bushnell dated November 15, 1938, listing each instrument to be sent to the Naval Observatory and the specific work that needed to be done. The first two pages of this memo are reproduced below. Item 12 on the list is 'Sextant, Brandis N.O. 1542 General Overhaul'. A note penciled into the margin indicates that this sextant was returned to the Bushnell on January 17, 1939. The ’N.O.’ is obviously an abbreviation for Naval Observatory [10]. So here in this memo it is documented that a Brandis sextant with U.S. Naval Observatory number 1542 belonging to the USS Bushnell was refurbished by Naval Observatory in late 1938 and was back aboard the Bushnell by January of 1939, about a year and a half after Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan went missing, and about a year before the Bushnell stopped at Nikumaroro to survey it. The sextant box found on Nikumaroro marked with the numbers 3500 and 1542 wasn’t Fred Noonan’s, it was a Brandis sextant box that a Bushnell surveyor happened to lose in the vicinity of the remains of the castaway’s final campsite.

|

| List of Items Shipped from the Bushnell to the Naval Observatory, Page 1 |

|

| List of Items Shipped from the Bushnell to the Naval Observatory, Page 2 |

|

| Marginal Note on Page 2 Indicates Items 11 through 15 Returned to the Bushnell on 1-17-39 |

Comments, corrections, additional relevant facts, differing viewpoints, etc., are always welcome. Send to gardnersghost@gmail.com

~~~

References

[1] Amelia Earhart’s Bones and Shoes? Current Anthropological Perspectives on an Historical Mystery. This report was ‘prepared for release’ at the 1998 annual convention of the American Anthropological Association. It can be downloaded at the TIGHAR website: https://tighar.org/Publications/TTracks/1998Vol_14/bonesandshoes.pdf

[2] The Nikumaroro Bones Identification Controversy: First-hand examination versus evaluation by proxy - Amelia Earhart found or still missing? Pamela J. Cross and Richard Wright. Journal of Archeological Science: Reports 3 (2015) 52-59.

[3] Amelia Earhart and the Nikumaroro Bones: A 1941 Analysis versus Modern Quantitative Techniques. Richard L. Jantz. Forensic Anthropology Vol. 1, No. 2: 83–98

[4] Actually, at this point the colonial officials thought that a sextant with the numbers 3500 and 1542 had been found, not just an empty sextant box, but the idea is the same.

[5] Noonan borrowed a Pioneer aviation bubble octant from the U.S. Navy. The signed receipt indicates it was to be used on the round the world flight with Amelia Earhart. A copy of that receipt can be found at: https://sites.google.com/site/fredienoonan/topics/pionneer-octant

[6] Tighar’s collection of Bushnell documents is available for download at: https://tighar.org/wiki/USS_Bushnell_Survey_(1939)

[7] Hydrographic Manual, U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey Special Publication No. 143. J.H. Hawley. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. (1931)

[8] My quotes come from Replies 40, 41 and 121 on the Seven Site Thread of the TIGHAR discussion forum (https://tighar.org/smf/index.php/topic,508.0.html). There were other insulting remarks and a strange degree of obtuseness about my hypothesis from Gillespie and some of his loyal followers.

[9] Toulmin’s report is titled: SEXTANTS AND NOONAN/EARHART: The Pensacola Fred Noonan Sextant and Box and the Amelia Earhart—Fred Noonan Disappearance and Sextant Research on the US Naval Observatory at the US National Archives. It is dated May, 2018. Mr. Toulmin’s report will be published on his website, www.themosttraveled.com, on the page on Finding Lost Airplanes. Until then it is available upon request at lewtoulmin@aol.com.

[10] We can be sure that 1542 was the sextant’s Naval Observatory number, not its Brandis serial number by looking at item 8, a Keuffel and Esser protractor, for which both the manufacturer’s number, K&E #10013, and Naval Observatory number N.O. #176, are given.